The

Five Ws and H are questions whose answers are considered basic in information-gathering. They are often mentioned in

journalism (

cf. news style),

research, and

police investigations.

[1] They constitute a formula for getting the complete story on a subject.

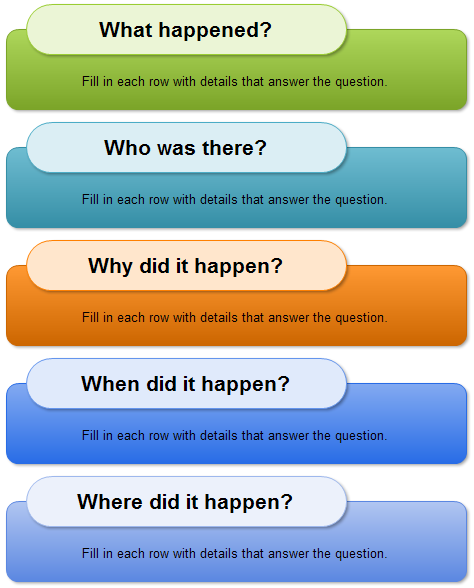

[2] According to the principle of the Five Ws, a report can only be considered complete if it answers these questions starting with an

interrogative word:

[3]

- Who is it about?

- What happened?

- Where did it take place?

- When did it take place?

- Why did it happen?

- How did it happen?

Each question should have a factual answer — facts necessary to include for a report to be considered complete.

[4] Importantly, none of these questions can be answered with a simple

"yes" or "no".

History

This section focuses on the history of the series of questions as a way of formulating or analyzing rhetorical questions, and not the theory of circumstances in general.

[6]

The rhetor

Hermagoras of Temnos, as quoted in pseudo-Augustine's

De Rhetorica[7]defined seven "circumstances" (μόρια περιστάσεως 'elements of circumstance'

[8]) as the

loci of an issue:

- Quis, quid, quando, ubi, cur, quem ad modum, quibus adminiculis.[9][10]

- (Who, what, when, where, why, in what way, by what means)

Cicero had a similar concept of circumstances, but though

Thomas Aquinas attributes the questions to

Cicero, they do not appear in his writings. Similarly,

Quintiliandiscussed

loci argumentorum, but did not put them in the form of questions.

[9]

Victorinus explained

Cicero's system of circumstances by putting them into correspondence with Hermagoras's questions:

[9]

Boethius "made the seven circumstances fundamental to the arts of prosecution and defense":

- Quis, quid, cur, quomodo, ubi, quando, quibus auxiliis.[9]

- (Who, what, why, how, where, when, with what)

To administer suitable

penance to

sinners, the 21st canon of the

Fourth Lateran Council (1215) enjoined confessors to investigate both sins and the circumstances of the sins. The question form was popular for guiding confessors, and it appeared in several different forms:

[11]- Quis, quid, ubi, per quos, quoties, cur, quomodo, quando.[12]

- Quis, quid, ubi, quibus auxiliis, cur, quomodo, quando.[13]

- Quis, quid, ubi, cum quo, quotiens, cur, quomodo, quando.[14]

- Quid, quis, ubi, quibus auxiliis, cur, quomodo, quando.[15]

- Quid, ubi, quare, quantum, conditio, quomodo, quando: adiuncto quoties.[16]

The method of questions was also used for the systematic

exegesis of a text.

[17]

Who, what, and where, by what helpe, and by whose:

Why, how, and when, doe many things disclose.

[18]

In the 19th century US, Prof.

William Cleaver Wilkinson popularized the "Three Ws" – What? Why? What of it? – as a method of Bible study in the 1880s, though he did not claim originality. This became the "Five Ws", though the application was rather different from that in journalism:

"What? Why? What of it?" is a plan of study of alliterative methods for the teacher emphasized by Professor W.C. Wilkinson not as original with himself but as of venerable authority. "It is, in fact," he says, "an almost immemorial orator's analysis. First the facts, next the proof of the facts, then the consequences of the facts. This analysis has often been expanded into one known as "The Five Ws:" "When? Where? Who? What? Why?" Hereby attention is called, in the study of any lesson: to the date of its incidents; to their place or locality; to the person speaking or spoken to, or to the persons introduced, in the narrative; to the incidents or statements of the text; and, finally, to the applications and uses of the lesson teachings.

[19]

The "Five Ws" (and one H) were memorialized by

Rudyard Kipling in his "

Just So Stories" (

1902), in which a poem accompanying the tale of "The Elephant's Child" opens with:

- I keep six honest serving-men

(They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who.

This is why the "Five Ws and One H" problem solving method is also called as the "Kipling Method", which helps to explore the problems by challenging them with these questions.

By 1917, the "Five Ws" were being taught in high-school journalism classes,

[20] and by 1940, the "Five Ws" were being characterized as old-fashioned and fallacious:

The old-fashioned lead of the five Ws and the H, crystallized largely by Pulitzer's "new journalism" and sanctified by the schools, is widely giving way to the much more supple and interesting feature lead, even on straight news stories.

[21]

All of you know about — and I hope all of you admit the fallacy of — the doctrine of the five Ws in the first sentence of the newspaper story.

[22]

References

- Jump up^ "Deconstructing Web Pages of Cyberspace".MediaSmarts. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- Jump up^ [1] Journalism website. Press release: getting the facts straight. Work by Owen Spencer-Thomas, D.Litt. URL retrieved 24 February 2012.

- Jump up^ "The Five Ws of Online Help". by Geoff Hart, TECHWR-L. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- Jump up^ "Five More Ws for Good Journalism". Copy Editing, InlandPress. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- Jump up^ "The Five Ws of Drama". Times Educational Supplement. 4 Sep 2008. Retrieved 10 Mar 2011.

- Jump up^ For which, see e.g. Rita Copeland, Rhetoric, Hermeneutics, and Translation in the Middle Ages: Academic Traditions and Vernacular Texts, 1995. ISBN 0-521-48365-4, p. 66ff as well as Robertson

- Jump up^ Though attributed to Augustine of Hippo, modern scholarship considers the authorship doubtful, and calls him pseudo-Augustine: Edwin Carawan, "What the Laws have Prejudged: Παραγραφή and Early Issue Theory" inCecil W. Wooten, George Alexander Kennedy, eds., The orator in action and theory in Greece and Rome, 2001.ISBN 90-04-12213-3, p. 36.

- Jump up^ Vollgraff, W. (1948). "Observations sur le sixieme discours d'Antiphon". Mnemosyne. 4th ser. 1 (4): 257–270. JSTOR 4427142. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Robertson, D.W., Jr (1946-01). "A Note on the Classical Origin of "Circumstances" in the Medieval Confessional". Studies in Philology 43 (1): 6–14.JSTOR 4172741. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- Jump up^ Robertson, quoting Halm's edition of De rhetorica; Hermagoras's original does not survive

- Jump up^ Citations below taken from Robertson and not independently checked.

- Jump up^ Mansi, Concilium Trevirense Provinciale (1227), Mansi,Concilia, XXIII, c. 29.

- Jump up^ Constitutions of Alexander de Stavenby (1237) Wilkins, I:645; also quoted in Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologica I-II, 7, 3.

- Jump up^ Robert de Sorbon, De Confessione, MBP XXV:354

- Jump up^ Peter Quinel, Summula, Wilkins, II:165

- Jump up^ S. Petrus Coelestinus, Opuscula, MBP XXV:828

- Jump up^ Richard N. Soulen, R. Kendall Soulen, Handbook of Biblical Criticism, (Louisville, 2001, ISBN 0-664-22314-1)s.v. Locus, p. 107; Hartmut Schröder, Subject-Oriented Texts, p. 176ff

- Jump up^ Thomas Wilson, The Arte of Rhetorique Book I. full text

- Jump up^ Henry Clay Trumbull, Teaching and Teachers, Philadelphia, 1888, p. 120 text at Google Books

- Jump up^ Leon Nelson Flint, Newspaper Writing in High Schools, Containing an Outline for the Use of Teachers, University of Kansas, 1917, p. 47 at Google Books

- Jump up^ Mott, Frank Luther (1942). "Trends in Newspaper Content". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 219: 60–65. JSTOR 1023893. Retrieved 2014-03-19.

- Jump up^ Griffin, Philip F. (1949-04). "The Correlation of English and Journalism". The English Journal 38 (4): 189–194.doi:10.2307/806690. JSTOR 806690. Retrieved 2014-03-19.